Gemma Pearson reviews The Empty Greatcoat by Rebecca F John, a fictional reimagining of the author’s great-great uncle’s experiences of war.

“You cannot claim an identity with a title. And yet, Sergeant House is the only man Francis knows how to be. Wearing a uniform, leading men, charging into battle, swallowing his fears, being alone, silencing his doubts, fighting with his fists, acting autarkically – this is what being a man has always meant.”

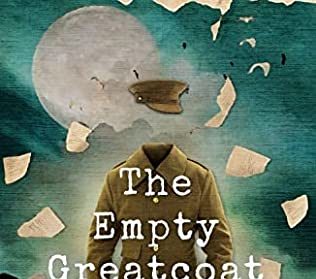

Set during one of history’s most grievous and futile military campaigns, Rebecca F. John’s The Empty Greatcoat transports readers to the dugouts of Gallipoli, where British, Australian, and New Zealand troops lay suspended in an eight-month stalemate against the Turkish army. The novel – the first release by Aderyn Press – is a speculative reimagining of John’s great-great uncle’s experiences of war, the details of which were scrawled in a “small, seaweed green notebook,” which John unexpectedly discovered as a teenager. Interspersing the novel with extracts of her ancestor’s own words, John creates a cohesive and symbiotic narrative that traverses generational lines. At its core, however, The Empty Greatcoat aches with heaviness; John writes about challenging issues such as opioid dependence, shellshock, guilt, and the lasting torments of trauma with a tenderness that feels particularly personal. What is more, when Sergeant House notices an eerie, hovering greatcoat – a sartorial spectre – observing him from afar, John’s narrative invites questions about the vacuity of war, of lives needlessly lost, and the inescapability of our pasts.

Having enlisted in the army at just fifteen years of age, Francis House is eager to follow in the footsteps of his father, a Boer war veteran. In the mind of a teenager, deployment represents adventure, opportunity, and valour. But, like his father before him, Francis quickly finds himself face to face with the grisly realities of combat: “War in no way resembles that which Francis dreamt of when he tucked himself into his childhood blankets […] and Francis had wanted this. Begged for it even.” Rather, Sergeant House must listen as shells rattle overhead, the sound of which “is as much a weapon as the shelling itself,” and watch as one friend after the next is fatally injured, “shattered to atoms”. With an effortless command of descriptive language, John gives life to the horrifying sights, smells, and sounds of war, drawing readers into the minds of the soldiers, each one “coming loose,” falling closer and closer to breaking point amid the inhumanity of their situation:

There is no room for bravery or heroism here. […] These soldiers have simply learned to stop opening their mouths to the gruesome tang of decaying flesh and disinfectant. […] So, this is Anzac, he thinks. It tastes of death.

Finding solace in the small things, however, John’s characters escape the violence and mundanity of military life through community and kinship. Sharing rations and clandestine cigarettes and reading letters from loved ones aloud to one another, Sergeant House’s men find a will to survive through tiny semblances of normality.

Moreover, while much of the novel’s action takes place on the same beach, The Empty Greatcoat does not feel static. John advances the plot with hazy, opioid-soaked episodes that challenge the form and structure of the narrative. It is perhaps also House’s repeated consumption of an opioid tincture that creates the psychological conditions in which a ghost-coat appears to haunt him:

A slip of cloud wreathes the moon, casting a net of darkness over the beach. The figure begins to rotate slowly. Francis looks to the sand, to avoid the immediate regard of the man standing beside the broken sloop and, where he expects to see a pair of scuffed boots, finds nothing. No boots. No feet. Nothing but the silvered air. And above that, no trousers, no belt, no vest. […] there is no man here. there is nothing but an empty greatcoat, and above the place where a man’s head should be, a hollow peaked cloth hat.

Although terrifying at first, House’s supernatural encounters soon facilitate something more profound. As the hauntings continue to manifest – each time more tangible than the last – Sergeant House finds strength to come to terms with a guilty conscience and to explore the deepest recesses of his selfhood.

Stories of young soldiers, from the boy-warriors of Sparta to the estimated 250,000 teenagers enlisted in World War One, reverberate with sadness. A stark symbol of lost potential and corrupted innocence, such accounts continue to captivate and disturb us in the present day. The empty coat – symbolic of the ostensible expendability of a young soldier’s life – therefore stands to remind us of the devastating cycle of violence immortalised by stories like that of John’s great-great uncle. Revisiting the treacherous beaches of Gallipoli, guided by the words of the real Sergeant Francis House, Rebecca F. John offers readers a raw ancestral story about loss, restitution, and the ghosts of our nation’s military past.

The Empty Greatcoat by Rebecca F John is available via Aderyn Press.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.