Does the concept of alienation work in the gallery space? If you are made to feel like an outsider before you have even entered the gallery, can you still find yourself endeared to the gallery’s contents? Is this loaded question a fair one, or should we succumb to the curator’s dictation? These issues are presented to us at the YU Gallery in Treforest, in the ‘Other’ Exhibition.

Various artists

YU Gallery, Treforest, Mid Glamorgan

‘The sameness of homogenous identity is the utopian ideal of socialist social formation that has historically succumbed to dystopia,’ states the exhibition’s introduction, offered so that the visitor can understand a bit about the overall theme of this show. Don’t worry if you didn’t get it the first time round – or the third – you’re not necessarily meant to. This thesaurus-

Whether it is worthwhile to alienate the very people who enter to view the art is another matter entirely. It comes down to one factor: whether the viewer realises they are being manipulated or not. Reading through the introduction of the exhibition, at first I was left perplexed by the density of the text as I didn’t get the idea (the art world loves ‘jokes‘ and humour, and will often substitute the reactionary for the thoughtful). My initial reaction was to dismiss the text as another statement using big words for the sake of using big words; it seems nowadays that (especially in conceptual art) the simpler the idea, the more text is needed to explain it. After a few re-

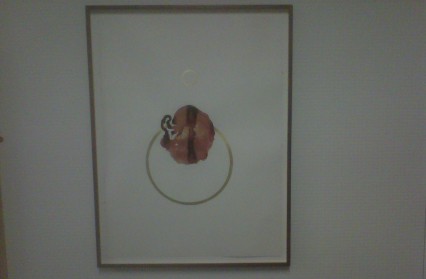

To be truly immersed in the piece is to forgo one’s pride and enter into a sense of heightened awareness of what the gallery space is intending to do. But this is easier said than done. It helps if the selected works are concrete with the theme of the show; as it happens, Ione Rucquoi’s ‘Placenta’, near the entrance, is a great curatorial choice in this respect. Following the birth of a child, Rucquoi created a print of her own placenta. Although this is not an original artistic or commercial endeavour (though each placenta is as unique as the baby it carried), it serves its purpose remarkably well. As placentas are essential to life then discarded in a gruesome mess when no longer needed, the essential paradox of tender violence leaves a mesmerising – yet ultimately dividing – immediate impression on the viewer.

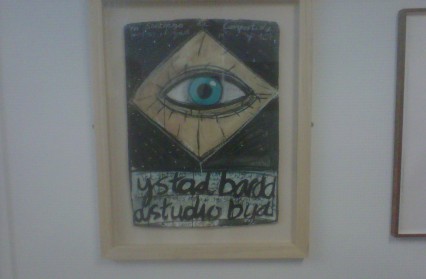

Next to Rucquoi’s ‘Placenta’ is Iwan Bala’s ‘Ystad Bardd, Santiago’. It is unusual to have two ‘impact pieces’ next to each other, but it is evidence of the quality of work collected by the curator that two delightfully good pieces should be so close. The picture is named after a dihareb, a Welsh aphorism that uses as few words as possible to create as large an impact as possible, and was coined in the 14th century by the poet Sion Cent. The bottom of the picture (beneath a large, near-

The purpose of this is to juxtapose the two languages with their currently purported postcolonial alignment. The primitive yet all-

Entering the main gallery space, the amount of work on display is truly staggering – leading to the impressive situation where the work shown is not only side by side but virtually on top of other pieces. My particular favourite is Bruce Risdon’s oil painting, ‘The Barrow Boy’, which shows a smiling nude man hiding his modesty with a well-

It is indeed when entering the main part of the gallery that the full idea of the ‘Other’ properly comes to life. One side of the gallery houses a traditional tea room; the other side holds an intimidating security office, with an open door, complete with a monitor showing the happenings in the rest of the gallery. Both rooms were purpose-

It is these pieces, with their subtle clues (why else would they be there except to stimulate thought?) which help hold the thematic issues of the show together. By squeezing and usurping the viewer’s idea of what the traditional gallery space should entail, the viewer feels included in the exclusion. But by ruthlessly alienating some and letting ‘Others’ find out the hard way, it could be argued that the show is for those in the know only. By not being fully immersed, it is far too easy to become distracted. This then leads to the situation where those in the know, by observing the perplexed and uncomfortable looking outsiders also viewing the work, actually transcend their own ‘outsiderness’. Thus by excluding one group and including another, the work ultimately meets its remit of playing people against each other. However, it does feel as if it is to the benefit of one group and to the detriment of the ‘Other’. While we may view art to see the world differently, it may be better to explore such issues in a more sympathetic way, to ensure the benefit – and enjoyment – of all.

Images from the exhibition