Nydia Hetherington and Tracey Rees-Cooke explore the legacy of William Blake at Tate Britain, London.

Everyone loves to wax lyrical about William Blake. From professors to poets to painters, panhandlers and popstars, Blake’s imagination remains hugely influential despite its limitations in his lifetime. As the Blake exhibition comes to a close, we are fortunate enough to bob along to a talk curated by John Higgs, whose small yet mighty collection of essays: William Blake Now was thoroughly enjoyed by both Nydia and Tracey.

Firstly, the context. It is January 31st 2020 – Brexit Day.

How apt to get a first peek at Mr Gee’s mistranslated-via-Google regrooving of Blake’s famous “Jerusalem”. Through his artwork “Bring Me My Fire Truck”, the outstanding maverick Mr Gee seeks to explore Brexit via Blake and it does indeed create a buzz. Symbolically displayed as an airport departures board, this witty yet disturbing piece of word art shows the text translating in front of the viewer via 23 official European languages, plus welsh.

It is beyond cool. Mae y tu hwnt cwl.

Meanings are reformed, regurgitated and reiterated through algorithmic patterns, verbal assumptions and inevitably corruptions of language.

We concede Blake would have loved it.

Throughout the debate, Gee radiates. He is enthusiastic about Blake and clearly quite mythical himself. His poetic ideas for re translation strike a chord and offer fresh insight into a poem which has become far closer to the establishment than William Blake ever did.

Throughout the debate, Gee radiates. He is enthusiastic about Blake and clearly quite mythical himself. His poetic ideas for re translation strike a chord and offer fresh insight into a poem which has become far closer to the establishment than William Blake ever did.

Londoner Nabihah Iqbal is currently an artist in residence at Somerset House. Blake’s London appears to reside within her DNA. She is a musician, a producer and a DJ; her inspired music video gives a touch of MTV to the evening. Iqbal connects to the Blake vibe of pounding ‘…the charter’d street, Near where the charter’d Thames does flow’. Her flashes of colour, her Pet Shop Boys-influenced synth pop disco beats reflect modern London – the urbanised shopping precincts, neo-thinker street style and blithe observations. Iqbal’s natural exploration of her environment transcends into her own vision and she presents it well.

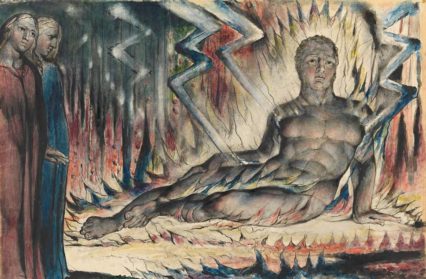

With no introduction Brian Catling, RA reads. It is resounding. He growls through Blake’s words with a deep resonance. We gasp. Catling clearly believes in “The Ghost of a Flea”. He becomes The Flea and he creates The Flea. Only his version of The Flea is not the theatrical, spotlighted, star spangled strutting monster we know from Blake’s small yet exquisite painting. Catling presents us with something far more gruesome, something more in keeping with our times, perhaps.

The sculptures, “Flea bowl” and “Flea bowl 2”, show the horror behind all the glitz of Blake’s vision. They are versions of the bug’s collecting cup; the receptacle in which the tiny creature would store, then feed on, the blood of its victims. No longer the size of an acorn, Catling’s are made large, made human size. They are steel and plastic, found objects from tool sheds, they are all twists and spikes and layers and as soon as we see what they are, they are terrifying.

Blake famously sketched The Flea as the vision appeared before him, explaining that the insect, speaking to him at the time, told him that fleas carry the souls of bloodthirsty men. Death, in diminishing these men’s proportions, saves the living from unmentionable cruelty. Catling’s Flea Bowls belong to behemoths then, who, given the chance, might drain the blood of whole countries. Somehow, tonight, this seems fitting.

That Blake saw visions and spoke with angels is well-known. John Higgs agrees that when speaking about William Blake it is impossible to ignore this. It is why he has been so often described as mad, or at best eccentric. But, says Higgs, we all have visions, we just have different ways to describe them. We think that sometimes, those of us who love Blake, find our own ways of dealing with his visions.

Iqbal, Gee, and to some extent Higgs, all seem to want, in some way, to get under the skin of Blake, to know the man. But as Catling points out, what we have of Blake now is an enormous body of work. We cannot know a man who died centuries ago, we cannot scrutinize his mental health under our modern psychoanalysis. We can read his work. Make it work for us.

Like Gee’s departures board and Iqbal’s pounding oral and visual cityscape, like Catlings flea bowl, Blake’s imaginings go everywhere yet nowhere. This seems entirely fitting, encapsulating our 21st century meta-age, perfectly.

We are all MELT!

Artists, writers and musicians―from Frank Turner to Bruce Dickinson―continue to immerse themselves in Blake’s life and work, whether they’ve read his, admittedly challenging, Prophetic Mythologies or not. This is a thread we also wander down and I wonder, as I look around the crowded auditorium, how many of us haven’t read The Book of Urizen, The Book of Ahania, The Visions of the Daughters of Albion, and others? I admit that I have not read them all closely. I , Nydia , the self-confessed Blake mega-fan!

The anti-authoritarian, dissenting voice of Blake we decide, as we sit in the dark nodding in unison, does indeed resonate today more the ever. With the rise of Extinction Rebellion, his vision seems more prescient than ever. Blake lived in a time of revolution and war, his voice rose above the jingoism, the bowing to church and monarch to a higher divinity, that of the imagination.

That Blake was critical of the institution of marriage as the enslavement of women, that he and his own most excellent wife Catherine, extolled the virtues of nudism, and that he was angered by the hypocrisy of the then all powerful Church, is well known. And yet, as part of Tate’s own exhibition, the image of Urizen was projected in massive proportions onto the front of St. Paul’s Cathedral. We wonder if Blake would be amused that his fallen angel, his very own version of Satan, is in the 21st century, writ large, bleeding in glorious technicolour all over the head architectural symbol of the Church of England, or would he scream in frustration that, although he now has more recognition now than he dared even imagine in his own lifetime, we still don’t get it.

We will never know.

ADDITIONAL INFO :

John Higgs is an English writer, novelist and cultural historian. He has a website, newsletter and can be found on twitter and Facebook. In addition to a new Blake book set for May 2020 , he has a newsletter : Higgs’ Octannual Manual which is pretty much a life essential whether you like Blake or not.

Nabihah Iqbal has an MPhil from Cambridge University on African history , experience in human rights and has a black belt in karate. You can watch her on youtube, hear her on SoundCloud and of course, find her facebook.

Mr Gee‘s post Brexit Day artwork is on display now : CopyThat?Surplus Data in an Age of Repetitive Duplication , Feb 2020 – Dec 2020 at the Open Data Institute

Brian Catling, RA is an English sculptor, poet , novelist , film maker and performance artist – he is Professor of Fine Art at The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art.