In the latest of a new series of Q&A’s with some of Wales’s leading artists, musicians, performers, and writers, Clive Hicks-Jenkins discusses growing up in Newport, his creative influences, and the art of collaboration.

Where are you from and how does it influence your work?

I was born in Newport in Gwent. Hard to say exactly how it’s influenced my work as an artist. Countless ways, probably, if you trace all the threads back to source. I loved the place as a child, and there’s a sort of ghost version of Newport in my head, which is how it used to be. I realise at this distance how rich Newport was architecturally back in the 1950s, and how the character of the place and its topographies of streets and hills and contrasting neighbourhoods have stayed with me. There was a fine covered market, a handsome and thriving high street with diverse businesses scattered about the town, wonderful old cinemas. There were the docks and the transporter bridge. In the small neighbourhood of Maindee where I lived, there were several small parks, a pint-sized library, a picturesque police-station complete with Dixon-of-Dock-Green blue lamp, my primary and junior school, a public baths and a cinema, all within an area you could circle on foot in thirty minutes. Later so much that was lovely was shamefully destroyed by ham-fisted planning and craven building developers. I remember my mother weeping when the bulldozers moved in on the old Lyceum Theatre at the bottom of Bridge Street. (Take a look at photographs to compare what was once there, to how it is now.) Both my parents were from the area and had deep attachments to its landscapes, so most weekends our family would go walking in Wentwood, the stretch of woodlands between Newport and Chepstow, having picnics and enjoying the views from the summit of Grey Hill. My dad had started his career as a land agent working for Lord Tredegar on the Tredegar Estate. However after the war he hated the way the tenant farmers were being treated as his employer sold off the land, so he left to become a wayleaves officer with the South Wales Electricity Board. During school holidays I’d accompany him as he criss-crossed the county and beyond, negotiating easements with farmers and landowners. That informed my eye. He informed my eye. He was a countryman through and through.

Where are you while you answer these questions, and what can you see when you look up from the page/screen?

I’m in the library/study at home. Warm grey walls, full bookshelves, art. A wall-mounted construction by my husband’s father, Dick Wakelin, a large Ernie Zobole landscape, a Ceri Richards ‘Heron’ print, a framed articulated maquette by Philippa Robbins and a preparatory drawing of mine for a book. My dog, Rudi, asleep in the armchair next to the window.

What motivates you to create?

At the heart of it, a need to make order out of chaos. (I’m talking about the universe, not the state of my sock-drawer!)

What are you currently working on?

Several illustration projects for a number of publishing houses, all of them for titles I can’t at this point reveal. Next year I have an exhibition at the Table Gallery in Hay on Wye to coincide with the Festival of Literature, which will focus on my work in the field of books. Then there’s a substantial exhibition, long in the planning, that will be the inaugural event at Oriel Myrddin when the current building work has been completed.

When do you work?

Every day. I like to start early when I can. But because the studio is in the house, I can work all night if it suits me or when deadlines are tight. There’s not much division between the various parts of my life at Ty Isaf. Work and maintenance of house and grounds intermingle, all flowing together.

How important is collaboration to you?

As an artist I’ve frequently drawn on literary sources. Even when working with a text by a dead writer, I regard the process to be a collaboration. When I’m taking something made by another person and reacting and adjusting to it, I feel a responsibility. When illustrating a book by a living writer, such as Simon Armitage, with who I’ve made three books and directed a stage production with a libretto by him, then the collaboration is necessarily more active. For fifteen years I’ve been designing the covers of books for the American poet and novelist Marly Youmans, and for many of those books have made black and white illustrations, too. Our relationship is tremendously close. We’ve been collaborating for so long that we imaginatively inhabit each others territories.

Who has had the biggest impact on your work?

I can’t give one answer to that. Life is not so simple. There are those whose early encouragement greatly helped me, chief among them the painter Dick Chappell who was generous with his practical advice. (Not all artists were as kind as he.) My partner – now my husband – Peter Wakelin, supported me as I became an artist. He took my work to the Kilvert Gallery, where the Late Lizzie Organ gave me my first exhibition opportunities. But before all this, in my earlier days, there were the many teachers and mentors who set me on journeys I may not have taken without their encouragements, and those who gave me opportunities which changed my directions at several critical points. There are the artistic influences to be considered too. The painters and makers, anonymous and known, who taught me how to analyse and appreciate. Film-makers – cinema has played a significant role in forming me as an artist – composers, poets, novelists, historians and philosophers. Animators and puppeteers, dancers and actors, directors and choreographers. I have been fortunate to have fallen under the spell of many brilliant creators who showed me ways forward. Some I have known in person. I’ve been very lucky in that respect.

How would you describe your oeuvre?

I am a narrative artist of diverse practices.

What was the first book you remember reading?

I remember sitting on my father’s lap as he helped me read a Rupert Bear annual. He was good teacher and I was an apt pupil, so I could read before I got to school. There weren’t a lot of books in the house, but such as there were I tore through. A few inherited ‘children’s’ books were on the shelves. I read a dense volume of Kipling’s short stories with not very exciting Edwardian illustrations that had been my father’s as a boy, and there was Ruskin’s The King of the Golden River in a slender edition illustrated by Fritz Kredel. My sister is six years older than me, and so I enthusiastically devoured her books because they were lying around, mostly novels about girls at boarding schools where the pupils had jolly adventures and illicit dorm tea-parties. Later when she started reading more adult fare, I got hooked on the Pan horror anthologies edited by Herbert Van Thal, read secretly by torchlight under the bedcovers because my parents wouldn’t have approved. I was madly keen on H. Rider Haggard and Edgar Alan Poe, and the Greek myths, thanks to my mother who pointed me toward them. I have an elegant edition of Myths of Ancient Greece Re-Told for Young People (Oxford, 1951) by Robert Graves and illustrated by the wonderful Joan Kidell-Monroe, and a later Larousse Encyclopaedia of World Mythology, both inscribed by my mother.

What was the last book you read?

The Mabinogi, in Matthew Francis’ poetic retelling published by Faber & Faber. (I’d kill to illustrate an edition of that!)

Is there a painting/sculpture you struggle to turn away from?

Hambeltonian, Rubbing Down by George Stubbs. It is the single most moving painting of a creature in extremis known to me. I’m mesmerised by the strangeness of it. I’d put it on a level with the Grunwald Christ. Stubbs homes in on the psychodrama underpinning the moment depicted. The racehorse is in a pose with both legs on one side raised, a stance not physically possible as it would just keel over. The artist knows that, but he does it anyway, because it’s right for the painting and the unease he wants to convey in this spectacle of an animal in a fearful state after a hard-won race. The handlers are tender, but Hambletonian’s ears are laid flat, his nostrils flared, he sweats and his lips are pulled back to expose his teeth. He’s clearly in a bad way after the terrible exertion. The painting was a commission by Hambletonian’s owner, the twenty-eight year old Sir Henry-Vane Tempest, who dissatisfied with it refused to pay the agreed sum to the seventy-five year old artist, claiming to the court in the case brought against him that his reputation as a racehorse owner had been called into question by Stubbs having portrayed the horse in a state of exhaustion. Unexpectedly given the times, the Judge ruled in the artist’s favour.

Who is the musical artist you know you can always return to?

Singer, Nick Drake. Composers, Philip Glass and Ravel.

During the working process of your last work, in those quiet moments, who was closest to your thoughts?

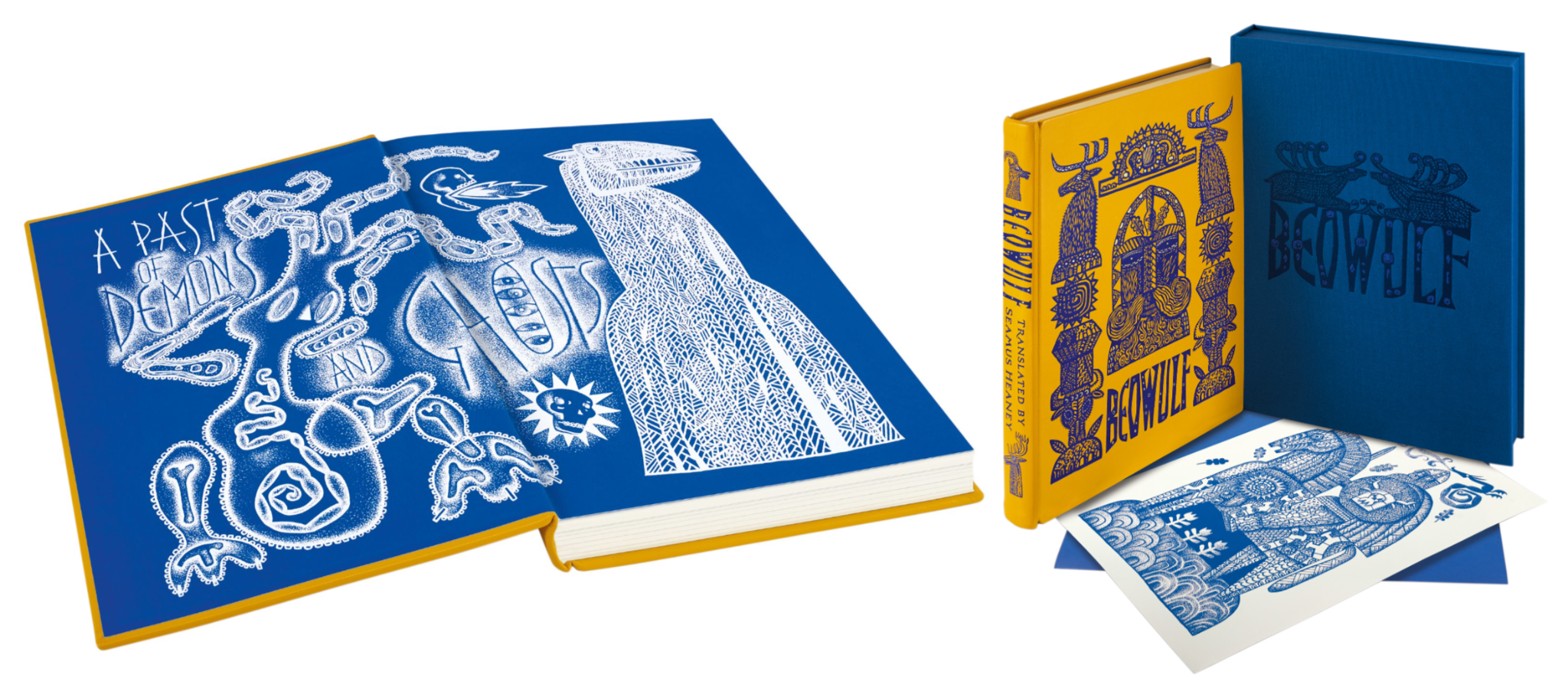

I was illustrating Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf in a new edition for Folio Society, so the text was at my elbow at all times. As I was constantly referring to it, I guess it could be said that Seamus Heaney was closest to my thoughts.

Do you believe in God?

No.

Do you believe in the power of art to change society?

I believe in the power of art to change myself. Society I’m less confident about.

Which artist working in your area, alive and working today, do you most admire and why?

If I’m candid, I’d be hard pressed to identify an artist working precisely in my area, given that I paint, illustrate, animate and direct. There can’t be that many. Also, I’m at that stage where so many of the people I most admired across the creative arts and looked to for inspiration, have died. Too many in the past few years. It broke my heart when Maurice Sendak passed, and Sondheim, too. Bowie and Glenda Jackson, gone. I can hardly believe it. These people were signposts and anchors for me.

What is your relationship with social media?

I harness it as best I can for work and making connections. It’s served me well for being able to reach out to people I admire, and that’s worked in both directions. Undoubtedly many of my projects of the past decade have had their foundations in collaborations begun online. I never liked or wanted to be a part of the way artists were traditionally presented by galleries in bibliographies, their lives reduced to lists of dates and achievements. In 2011 Lund Humphries published my monograph, for which I steadfastly refused to produce a bibliography. Instead I contributed a biographical chapter in which I presented, if not the definitive account of my achievements, then something which gave a sense of the journey. Since 2009 I’ve run a blog, the Artlog, at which I write candidly about my practices, my life, people I admire, collaborations and works in progress. In so many ways social media has deconstructed the tired old clichés of how things were once done, and as a consequence given artists – or the ones who choose to engage – the chances to speak for themselves.

What has been/is your greatest challenge as an artist?

Getting up to speed quickly when faced with unfamiliar challenges is always a thing. But at this stage of my life I believe it’s fine when undertaking something for which I’m only partially equipped, to say “Look, I can do most of this, but these are the areas I’ll need help with.” I’ve been working for publishing houses over the past few years on several big projects, and I always kick off by saying to the art directors “You know I’m a dinosaur, right? I don’t do digital and so everything you’ll be getting will be analogue, made with hands wielding brushes, pencils and pens.” And it always is alright. I work with really skilled technicians. Laurence Beck has been my clean-up artist and colourist at Design for Today for two books, Simon Armitage’s Hansel & Gretel: a Nightmare in Eight Scenes and Olivia McCannon’s Beauty & Beast. In the past couple of years I’ve worked very closely on publishing projects with David W. Slack, who is an artist in his own right, but has collaborated with me as a model-designer and maker, and recently worked as Animation Producer on the two films we were commissioned to create by Folio Society to promote Beowulf. Back in 2016 I was invited by Dan Bugg at Penfold Press to work with him on my first screenprint, a process that to begin with utterly bewildered me. But Dan guided me through it all, and since then we’ve completed a phenomenal body of work, including the fourteen-print series that went on to accompany Simon Armitage’s acclaimed translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in the 2018 Faber & Faber illustrated edition.

Do you have any words of advice for your younger self?

It’ll all be alright in the end.

What does the future hold for you?

I have enough exciting projects to keep me gainfully occupied for several years. Every time I think that maybe my moment has passed, then someone new comes knocking with a wonderful suggestion/opportunity. (One came yesterday with a proposition so exciting I didn’t sleep all night.) I’m grateful for that. It would be a good way to end one’s days would it not – hopefully some way down the line from here I should say – with something interesting in the pipeline? I don’t think I’d last long if the days stretched emptily ahead. I don’t know whether it’s true, but they say sharks have to keep swimming in order to stay alive. I think that might apply to me.

Clive Hicks-Jenkins latest work is a limited-edition illustrated edition of Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf for the Folio Society. More information is available here.

(Header photo credit: Joanne Crawford)

Clive Hicks-Jenkins Clive Hicks-Jenkins Clive Hicks-Jenkins Clive Hicks-Jenkins Clive Hicks-Jenkins Clive Hicks-Jenkins Clive Hicks-Jenkins Clive Hicks-Jenkins Clive Hicks-Jenkins Clive Hicks-Jenkins Clive Hicks-Jenkins