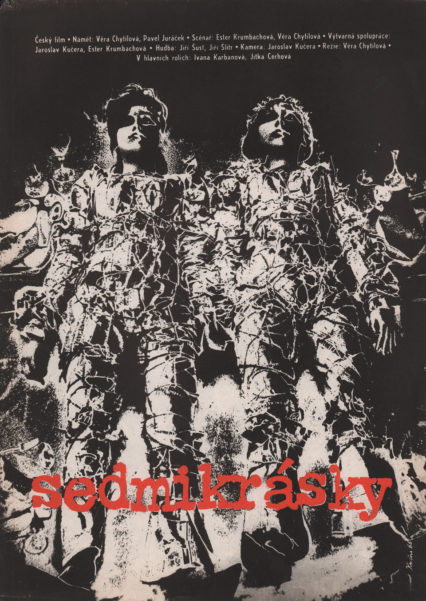

John Lavin looks back to 1966 in his review of Vera Chytilová’s seminal cinematic work, Daisies (Sedmikrasky).

Vera Chytilová’s second film was released in 1966 and immediately banned by the Communist government of Czechoslovakia. In England, 1966 was the year pop art went supernova. The year of Revolver, ‘Hey Joe’ and ‘Paint it Black’; the year Michelangelo Antonini decamped to London to immortalise the swinging Sixties in Blow Up. In Czechoslovakia, however, The Beatles and the Stones were still mostly a word of mouth phenomenon and the Czechoslovakian Communist Party, while undergoing a period of liberalisation, was still very much the Czechoslovakian Communist Party. And yet, with Daisies Chytilová, not long out of film school, created a sustained piece of revolutionary pop-art brilliance which is the equal of any of the works mentioned above. A work so high on life and so fuck you with the brilliance of being young and alive that it feels like a direct manifestation of Dylan’s ‘Your sons and your daughters are beyond your command / Your old road is rapidly ageing / Please get out of the new one if you can’t lend your hand…’

The opening credits switch between a large flywheel slowly cranking round and round and aerial shots of bombs exploding – instantly calling to mind Vietnam. In this and in the odd, discordant wooden xylophone accompaniment, Chytilová recalls Bergman’s Persona – with its footage of a self-immolating monk protesting against that war -which had only come out months earlier. We then meet Marie I and Marie II, the two young women who are the film stars, two women it should be said who are very different indeed to Alma and Elisabeth in Persona. All of which begs the question, is Chytilová poking fun at Bergman’s high seriousness even as she pays homage to his cinematic brilliance? The answer, for me, is almost certainly yes. Lying in skimpy bikinis in what appears to be a sauna, their every movement is accompanied by a mechanical squeak.

‘I can’t do anything well. A doll. I’m a doll. You understand?’says Marie II. The two women each comment on how the world has all gone bad before the thought slowly dawns on each of them that this being the case, they must have gone bad themselves. With rampant glee, they tumble out of the b&w sauna into a verdant garden shot in Technicolor, and full of daisies. In its centre, there is an apple tree studded with fruit, but Marie I comes away with a peach instead of an apple. Once again we see Chytilova’s irreverence. This film is not going to play things by the rules. It is not going to straightforwardly re-examine the story of the Garden of Eden from a feminist perspective. By having Marie I take a peach and not an apple from the tree Chytilová is simply saying: I can’t be bothered with all this nonsense. I haven’t got the time.

And so Daisies, a film with little or no regard for the traditional cinematic rules of time, begins its rampage. What follows is a series of scenes in which the two Marie’s either behave outrageously in various high-end establishments or play with the feeling of various wealthy older men in a way that the men themselves might more commonly be expected to treat two beautiful young women. This culminates in a scene in which Marie I leaves a man desperately professing his love to her on the telephone while she and Marie II precede to cut up various phallic-looking food items with a large pair of scissors.

This is followed by an extraordinary visual scene in which the two women, having had an argument, cut off various pieces of each other’s bodies until they are left as two talking heads. At this point, everything on screen is cut up and jumbled by Chytilová so that it looks like a Bridget Riley painting. (Earlier in the film the two Marie’s wear co-ordinated monochrome dresses which recall Riley’s Where.) Technically stunning for a film made at this time and on a low budget it is also the one moment where Chytilová, in suggesting human beings inherent interconnectedness with each other and their surroundings, allows space for a more typically sixties, peace and love poeticism to emerge.

If much of the film seems taken up with an anarchic brand of feminism, the climax of Daisies, returns us to the film’s opening assertion of individuality over Communist ideology. Discovering a vast banquet in an empty hall the two women set about eating, drinking and ultimately destroying everything in front of them, until finally they pull a chandelier out of its socket and come crashing down to earth.

After a scene in which they are repeatedly ducked underwater as punishment we return to the empty hall; only this time it is shot in the B&W of the opening sauna scene. The two Marie’s, each wearing dresses made from newspaper (recalling the fate of Joan of Arc), try to fix things by heaping the remains of the food back onto the silver platters and by fitting the shattered dinner plates back together, all the while chanting ‘We’re really happy’ like contrite communist party members (or stereotypical housewives). Chytilová seems to be suggesting that the Communist party (and perhaps men in general) prize appearance over everything else and that it is fine by them if corruption – as illustrated by the huge mounds of spoiled food – goes unnoticed.

Lying down on a parallel table the two Marie’s say to one another:

M I: ‘But we’re not really happy.’

M II: ‘We can pretend to be.’

M I: ‘Okay we’re really happy!’

MII: ‘But it doesn’t matter!’

And with that the rooms other chandelier falls on top of them, chiming with the sound of explosions from the opening credits. Against a bomb-blasted landscape, Chytilová types her final, punk rock kiss-off:

This film is dedicated to all those whose sole source of indignation is a trampled-on trifle.

It is not difficult to see why the Czech government immediately banned Daisies, so overt is it in its criticism of communist ideology and patriarchal hierarchies. Indeed for many years, Chytilová was prevented from making films altogether and Daisies was a seldom-seen film. Its reputation is, however, very much on the rise and it was shown recently at Chapter Arts Centre as part of their Story of Film season. Although no more showings are planned at the moment it is available on DVD and demands to be seen.