Jim Morphy reviews Into the Abyss, an award-winning documentary film written and directed by Werner Herzog.

‘Why does God allow capital punishment?’ Werner Herzog asks a prison chaplain in the prologue to Into The Abyss – this being a documentary, like much of the Bavarian’s work, that encourages participants and viewers to confront the dark and difficult questions of life and death that are buried within all of us.

The chaplain admits he doesn‘t know, and proceeds to give an answer taking in the local wildlife that the director seems to find unsatisfactory.

‘Please describe an encounter with a squirrel’, Herzog then says to the chaplain. This request elicits a tearful, meandering response about the wonder of existence and the horror of seeing people die, revealing to the viewer, and perhaps the man himself, a glimpse inside the chaplain’s heart.

Herzog’s documentary films are laced with this genius technique: offbeat questions bringing about responses that strike at the core of the deepest issues. And in dealing with murder and capital punishment, the brilliant Into The Abyss explores the very blackest of concerns.

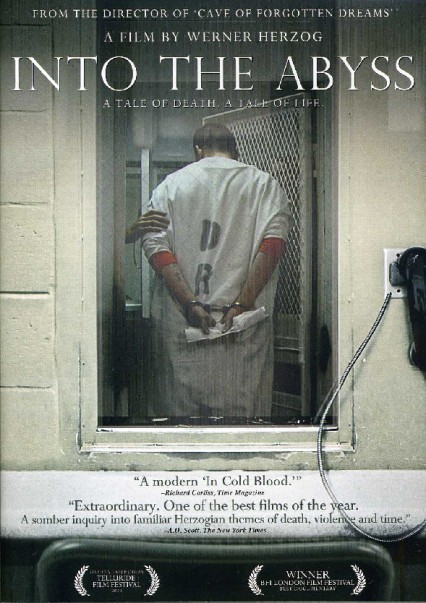

Herzog was researching for a documentary series about the death penalty when he came across a story he deemed worthy of telling in its entirety. The result is a film stemming from horror and distress, but which is shot through with the director’s customary sense of gentle humour and deep humanity.

Revolver Entertainment

Directed by Werner Herzog

In Texas in 2001, drunk, homeless teenagers Michael James Perry and Jason Burkett murdered Sandra Stotler in her home in order to steal her sports car. In making their escape, the two also killed Stotler’s stepson and his friend. The triple homicide resulted in Perry being given the death penalty and Burkett sentenced to life in prison.

Herzog examines this horrendous crime, and the spider’s web of its effects, by talking to a wide cast of people connected to the case, including the investigating police officer, Stotler’s daughter, Burkett’s incarcerated father, Burkett’s wife, a former captain of the nearby prison’s ‘Death House’, and the killers themselves.

As Herzog prods and probes around crime and punishment, it becomes apparent that rather than being fixated on the facts of the case, he is more interested in discovering the humanness in, and the essential ‘truth’ of, each individual. The director offers each of the interviewees the opportunity to state their case on what they did and why they did it, and what they believe and why they believe it. Everyone is granted respect, even if they are unlikeable. Herzog does not pass judgement, he is here to stimulate and record. Indeed, the director is a lot less visible than in many of his films. He remains out of shot, and there is no heavy voiceover. The people tell their stories.

We do hear the giant German’s kindly-

Herzog’s encounter with the former captain of Huntsville Prison’s Death Row provides one of the film’s most moving passages, and a tale that can be seen as the film’s moral centre –

Jim Morphy is a critic and regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.