Centenary Exhibition of Sculpture

National Museum, Cardiff

Image: courtesy of the Estate of Ivor Roberts-Jones.

No genre in art is as potently public as sculpture. In March barricades were formed in Kharkiv to protect a statue of Lenin against assault. At least a hundred have been felled across Ukraine since February. What surprises is less the demolition than the fact that so many have survived for so long. Oswestry-born Roberts-Jones was commissioned well into his career as a sculptor to take on great public figures, albeit singly: Apsley Cherry-Garrard in 1962, Augustus John in 1964, Viscounts Slim and Alanbrooke, Attlee for the Palace of Westminster, Churchill for Parliament Square.

The exhibition at the National Museum is the polar opposite of this public monument-making. A single first floor room houses twenty-six works, mainly busts. The height of the displays moves between eye level and chest-height. It makes for a particularly intimate, close-up relationship with Roberts-Jones’ subjects. The closeness is reminiscent of Dannie Abse when he stood beside a Dylan Thomas head for a television documentary. He saw an ‘astonishingly wild and haunted Dylan head staring into space, his tie awry, a cigarette drooping between his lips. The dead’ said Abse ‘can sometimes come alive for a moment.’

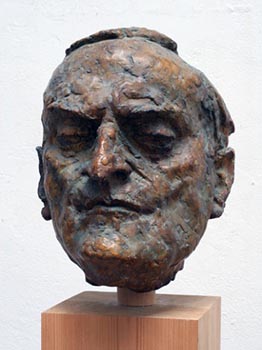

It is in the nature of sculpture that it tends towards the Great and the Good. A line of figures down the right-hand wall features the family names of Tyrell-Kenyon, Windsor-Clive, Paget, Crawshay and Twiston-Davies. But the treatment is far from hagiographical. Roberts-Jones himself spoke of capturing what he termed ‘the double edge’. So a William Crawshay of 1973 has pursed lips beneath a strangely leftward gaze. Tony Twiston-Davies has a sensitivity to the modelling in the deep-set eyes beneath the large eyebrows.

The furthest wall has a trio of political heavyweights, James Callaghan, Cledwyn Hughes and George Thomas. It is a testament to the elusiveness of expression, or perhaps post hoc facto revelation, that the last is endowed with a thin cruelty to the lips. By contrast, the adjoining figure, Geraint Evans, has a far-away dreamy expression.

Image: courtesy of the Estate of Ivor Roberts-Jones

It is also the nature of sculpture for its subjects to be marked more by age than youth. For the art it is no great disadvantage; the face in antiquity acquires shapes and folds that are absent in youth. Sir Cennydd Thaherne is pained in expression with an angled mouth beneath the hooded eyelids. The viewer has to stoop to see fully Sir Alun Talfan-Davies; he is aged eighty-one and Roberts-Jones has spared nothing in the eyelids that sag and the cheek muscles that droop.

The viewer has to stoop again to see actor Hugh Griffith. The great bushy brows are familiar from films like the zesty 1966 heist film How to Steal a Million. But it requires the viewer to drop to see properly the unmistakable eyes. Stylistically, the selection varies in treatment in a way that plays on the ambiguities in human expression. There is a hint of a Giacometti curve to one of the earlier works. Roberts-Jones brings a touch of playfulness to Kyffin Williams. Menuhin is depicted in a tilted-back posture with the head asymmetrically modelled.

This exhibition, marking the centenary of Roberts-Jones’ birth, is largely drawn from the Museum’s own holdings. Other works are on loan from the Glynn Vivian, Oriel Ynys Mổn and Arts Council of England. It is the reverse of the blockbuster. It is lightly publicised, easily grasped in overview, low on curatorial declamation. For these or other reasons it has proved to be an exhibition of some popularity. It is a popularity that is well-deserved.

The exhibition continues until 11th May.