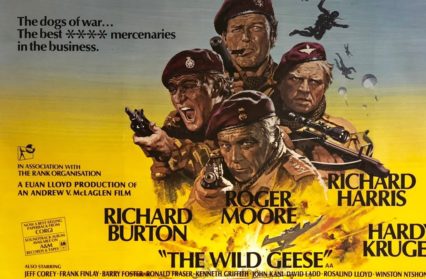

The ‘Becoming Richard Burton’ / ‘Bywyd Richard Burton’ exhibition is now reopened at the National Museum Wales and Wales Arts Review is publishing a series of essays to run concurrently with the exhibition, curated by Daniel G. Williams, director of the Richard Burton Centre at Swansea University. Each essay will discuss a specific Burton film; this week, Dr Gethin Matthews examines The Wild Geese (1978).

The Wild Geese was, by my reckoning, Richard Burton’s forty-sixth film and the eleventh in which he took the role of a military man. It was shot on location in South Africa in 1977, with additional filming at Twickenham Film Studios. In many ways it has not aged well. The first and most glaring point is that the film is imbued with condescending racism and misogyny. The second is that the violence is glorified and unrealistic. A third observation is that too many of the characters are caricatures, one-dimensional and the result of lazy scripting. Nor do some of the plot developments stand up to close scrutiny. Yet despite these obvious failings of form and content, there are some memorable flashes of action or dialogue and occasional sequences which stick in the mind. For me, there is a guilty pleasure in putting the brain into neutral and viewing Burton and his co-stars, Richard Harris and Roger Moore, go through their paces as the bodies pile up around them. Like a number of Burton’s films in the 1970s, The Wild Geese is immensely gripping and deeply problematic.

The film bears some superficial similarity to the 1968 blockbuster Where Eagles Dare. In both cases, Burton leads a team of soldiers on an improbable mission into hostile territory to rescue a valuable hostage, and twists and betrayals make the escape much more problematic (and exciting) than expected. Fans of movie trivia might also note that Brook Williams (Emlyn Williams’ son) accompanies Burton on both these adventures (although, in contrast to Where Eagles Dare, in which Williams is the first of the crew to get killed, in Wild Geese he makes it onto the plane home). The film begins in London by setting up the mission: Burton is Allen Faulkner, a mercenary colonel who is offered the task of rescuing Julius Limbani, a politician held captive in southern Africa. The mission is financed by Sir Edward Matherson (Stewart Granger), a capitalist who covets mining rights in the country. (Fans of movie trivia might wonder whether the obvious antipathy that Matherson shows towards Faulkner was heightened by the fact that back in the 1950s Burton had an intense affair with Granger’s wife, Jean Simmons).

The London scenes establish the characteristics of the trio of principal protagonists, including some traits that chime with their on- or off-screen personae. Allen / Burton declares ‘I work for anyone: it is an irredeemable flaw in my character’ and ‘My liver is to be buried separately, with honours’ as he downs a whisky. Janders / Richard Harris is the idealist, passionate and principled: he could be Cromwell, or a Man Called Horse. Fynn / Roger Moore, taking a sabbatical from bedding blondes as James Bond, gets into hot water when he eliminates a drug dealer responsible for the demise of one young girl, but is assisted in his escape by a glamorous girlfriend. She gets her face bashed in for her troubles: anyone looking for depth of female characterisation in this film will be disappointed. Quentin Tarantino succinctly described Where Eagles Dare as a ‘bunch of guys on a mission movie’, and that is what you have here, too.

The mercenary brigade is recruited from some lazily differentiated misfits, and then they are off to Africa for a spot of training before the mission proper begins. The crew fly into enemy territory and the body count begins to soar, and often in a troubling way. Cuban and African officers are slaughtered by machine guns in the enemy HQ, and a dozen guards are poisoned by cyanide in their sleep.

Having disposed of a score of soldiers who might have stood in their way, one wing of the mercenary troupe gets their target, Limbani, out of his cell while the other bloodily takes the airstrip. The plane to extract them comes in and lands, and there is a double-cross: back in London Matherson gets his mineral rights from the current regime and so the plane is ordered to leave the mercenaries stranded.

Janders/Harris comes up with a new plan, but as the convoy of commandeered trucks tries to escape across the country, one vehicle is strafed and bombed, and the mercenaries suffer their first casualties. It is not entirely clear why the group then splits up, nor how they know to navigate to the rendez-vous in this hostile territory, but the division into smaller groups does lead to the film’s set-piece philosophising. Janders / Harris, the mercenary with a moral compass (though also the instigator of the slaughter-by-cyanide) agonises over how to extricate themselves from their position without sparking a murderous civil war. The film’s most explicit philosophical message comes in the conversation between the Afrikaner mercenary Pieter Coetzee (Hardy Krüger) and Julius Limbani (Winston Ntshona). Previously, Coetzee’s remarks have established him as sharing the racial bigotry one might expect from a South African at the height of the Apartheid era, but in a break from their escape, they discuss whether blacks and whites could have a shared future on the continent. Limbani, the idealised African visionary, declares ‘We have to forgive you for the past, and you have to forgive us for the present. If we have no future together, white man, we have no future’. Perhaps in the 1970s this sounded like enlightened thinking on the road to reconciliation, but it does absolve the white folk in the present from responsibility for colonial brutality in the past and the continued legacies of racism and territorial annexation in the present.

Reports about the film, both in contemporary newspapers and in later biographies of Burton, offer the fig leaf that on set the production treated everyone equally well. The producers were adamant that, regardless of the Apartheid laws, the crew filming in the Transvaal should include a number of black workers who received the same pay and conditions as the white workers. Indeed the black actor John Kani, playing a mercenary, gave an interview in which he strongly defended the film’s attitude and message. Yet in retrospect this fig leaf does not spare too many blushes. No-one could have been unaware that South Africa had a pariah regime and anyone associated with it was tarred. In 1976, twenty-seven African countries had boycotted the Montreal Olympics because New Zealand was competing while their rugby team was touring South Africa.

In fact, the film never tries to go beyond the lazy prejudice that the default situation for black African rulers is to be cruel despots. The character of Limbani is portrayed as the sole example of a worthy and virtuous African leader. From the opening title sequence, which has a montage of Africans being abused by oppressive black forces, the vast majority of black extras in the film have a very short appearance which ends nastily. Limbani’s nemesis, General Ndofa, is referred to in a way which would make the 1978 audience think straightaway of Idi Amin, the brutal, evil, dictator of Uganda. General Ndofa’s troops are bloodthirsty and violent, and there is a telling moment in the escape when the film’s attitude towards Africans is crystallised. The mercenaries’ medic, Witty (portrayed crudely as an effeminate gay man) is surrounded with a jammed gun by a posse of armed enemy soldiers, but instead of shooting him, they gleefully machete him to pieces.

Yet if one can put aside the unsavoury attitudes towards the value of others’ lives, and for most it will be a big ‘if’, these sequences when the mercenaries are forced in extremis to depend upon one another are riveting. My favourite line is when the grizzled Sergeant-Major declares to the youngster under his care, ‘You’re not dead till I tell you you’re dead’. Others have picked the farewell line of the Irish missionary (Frank Finlay in a brief over-the-top cameo): ‘Good luck to you Godless murderers’.

Despite the story’s obvious flaws and weaknesses, the fact is that the performances of the three main characters make this a watchable and, for this guilty viewer, an enjoyable film. This was the only time that the three appeared together on the big screen, and that is the cause of regret: without a doubt Burton and Harris acting together with a thought-provoking script could have been electrifying. The pair’s final scene together continues to pack an emotional punch. This film marked Burton’s final outing as a soldier, and in fact this was his last box office success. He died before filming could begin on the execrable Wild Geese II, which is in retrospect a blessing in disguise for his reputation. Any full assessment of Burton requires us to engage with films such as The Wild Geese. It testifies to his electric screen presence, his under-rated brilliance as an ensemble actor, and to the racist and misogynistic seams that can only tarnish the continued status of his contested screen legacy.

Dr Gethin Matthews is a Senior Lecturer in the History Department at Swansea University. His first book was Richard Burton: Seren Cymru, a Welsh-language biography published in 2002.

Read last week’s Becoming Richard Burton essay here.