Do you think of 1977 as the year Welsh art was revolutionized? You ought to. At the National Eisteddfod that year, in Wrexham, the late artist Paul Davies staged a protest as a performance piece. There was a prevailing lack of recognition for political art works in Wales and he intended to change this. It led him to found a group of artists who became known as The BECA Group.

The name was inspired by the ‘Merched Beca’ or ‘Becca’s Daughters’, the Rebecca Rioters of 1839-43. Merchaid Beca would destroy toll gates that were put on Welsh roads by the English as a means of charging yet more taxes on already struggling farmers. This unfair taxation affected mid and south Wales’ agricultural communities in particular as they were already in dire poverty at this time due to poor harvests. Merchaid Beca intended to change this. Although they are referred to as Merched – Daughters, they were in fact men dressed as women, mostly farmers. In an early example of performance protest, they wore the traditional Welsh Lady costume, blackened their faces with soot to maintain anonymity and stealthily left their families, riding out on horseback into the night.

The name ‘Rebecca’ was taken from an obscure verse in the Bible, with which Wales’ non-conformist communities would have nevertheless been extremely familiar:

And they blessed Rebekah and said unto her, Thou art our sister, be thou the mother of thousands of millions, and let thy seed possess the gate of those which hate them. Genesis 24:60

One act of gate-breaking by the rioters included a protester acting as an old lady – a ‘mother’ who talks to her ‘children’ – the rioters. Something blocks the mother’s way; she is old and cannot see well. Her children are concerned; nothing should restrict their mother. They offer to move it for her, she feels the object and realises it’s a gate put there to stop her. The children, offended, offer to break it down, but Rebekah has faith and looks to see if it can be opened; to her horror it has been locked and bolted to which the children insist: ‘it must be brought down, mother; you and your children must be able to pass’ to which she replies: ‘Off with it then my children’. It becomes clear here that for the rioters, Rebekah is a mother symbol; the mother of the land -and the people of the land are her children.

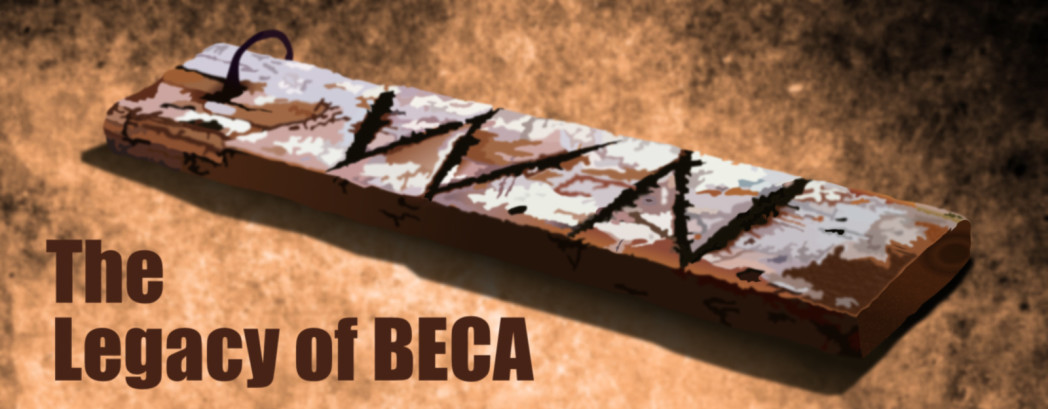

Paul Davies’ performance/protest at the 1977 National Eisteddfod not only echoed the theatricality of the Rebecca Riots, but also symbolically recalled another injustice with deep resonances, particularly in the Welsh-speaking community. Davis held a railway sleeper above his head in the grounds of the Eisteddfod. Inscribed on the sleeper were the initials ‘WN’, a reference to the punishments given to pupils when Welsh was spoken in schools in the wake of the 1847 education report that became known, notoriously, as The Treachery of the Blue Books. The same ‘WN’ initials were worn on a board hung around the child’s neck: Welsh Not.

Paul Davies’ performance/protest at the 1977 National Eisteddfod not only echoed the theatricality of the Rebecca Riots, but also symbolically recalled another injustice

To parade these initials at the National Eisteddfod of all places in Wales took courage and confidence; it was action certain to attract attention and shock both the public and the Eisteddfod officials. The Beca Group members Paul, Peter, Ivor and Tim Davies, Iwan Bala and Peter Telfer, all renowned Fine Artists in their own right, formed as Welsh artists were struggling to get their works exhibited within the galleries of Wales. This applied particularly to art inspired by political issues, as suppose to pictorial art. This was totally barbaric to the Artists, but also to the people of Wales and other visitors. Political art teaches the viewer of the issues Wales have faced or are facing.

The performance was a success. The organisers of the National Eisteddfod, the Arts Council of Wales, changed their dated view on Welsh art. Now the Eisteddfod actually encourages art of a political nature by rewarding artists with an Ivor Davies Award for art that conveys the spirit of activism in the struggle for language, culture and politics. The legacy of BECA is secure.

But if this was a revolution in Welsh art, how could we have not known about it before? Now that we have learnt about this exciting, inspiring and confident Art Group, you may be feeling inquisitive. Want to learn more? Unfortunately but not surprisingly there is a lack of information on the Beca Group. As a nation, we struggle to possess our success. Here, the BECA Group have changed the way visual art is thought of in Wales, but what about all those who didn’t or couldn’t go to the Eisteddfod that year, or like myself weren’t even born. The people of Wales shouldn’t be living life oblivious to the rare occasions where there have actually been positives in our history.

Artists create to deliver a message, to get it out there, at the Eisteddfod and beyond. There is nothing clever in making art hard for people to access. The BECA Group, Arts Council and the Eisteddfod had a responsibility in making the nation know about this. People at Eisteddfodau are less in need of being made aware of such issues; it’s the people who do not attend the Eisteddfodau who are the most in need of these eye openers. Is it just snobbery to only show themselves at Eisteddfodau? To be truly political, art needs to take to the streets.

There is nothing clever in making art hard for people to access.

Wales as a nation has been fighting for the survival of the Welsh language throughout its history, and yet we struggle to communicate in that very language. Why?

Throughout Wales there are many dialects. Slang differs not only between North and South but from village to village; then there are those who through higher education or via their parents learnt the ‘proper Welsh’. Many of us drift through life not really knowing about our own past, let alone our future as a nation. The main reason for this is most likely to be the fact that there isn’t one thing the whole of Wales watches, listens to or reads. The English have much influence on the Welsh language due to this. Could art be the answer in uniting us together? I’d like to think so.

The advantage of fine art is that there is no official person standing there telling you what to think and feel. It doesn’t tell you anything; it makes you ask questions: the most importance question being, what is the artist trying to say? This is instantly thought provoking. When we look at art we think in the language we speak so there is no intimidation for the viewer; art lets you make sense of it the best way it suits you, and relate the subjects to your own life experience, making it easier to digest. This results in a deeper level of understanding, and when you understand something, you gain confidence. Unlike music, film, or books, which all use words or tone to encourage a particular thought or feeling, fine art is respectful of its viewer. It does not tell you what to think; it merely encourages you to think, opening the mind. Art can help Wales to break down communication barriers or the so-called ‘cliques’ we seem to have in Wales and the Welsh ‘scene’.

The legacy of the Beca Group lives on as the voice for Welsh art. Whether the political artist of today is aware of the BECA Group’s actions or not they are most definitely responsible for created a strong and confident climate for these artists; they have secured a future for the politicisation of Welsh art. Welsh artists such as Bedwyr Williams, who will be representing Wales at the Venice Biennale 2013, and Carwyn Evans, who won the gold medal at the National Eisteddfod 2012, have definitely got the BECA Group to thank for the opportunities leading to their own successful careers.

The success of the BECA Group is no surprise when looking at the members’ subsequent achievements:

The late Paul Davies founded the BECA Group during the 1970s and his image at the ‘Welsh Not’ performance is the most iconic image of contemporary Welsh art. The issues that caused concern for Davies were history, identity and the condition of the environment of his land. Davies wanted to teach and inspire people of the issues surrounding Wales and hoped to stimulate a movement. In his efforts to do this he involved everyone from students, the unemployed, to the disabled and children. Davies created maps of Wales in a variety of different mediums and was said to have drawn a map of Wales a day. Peter Davies, brother of Paul, is an artist, lecturer, and curator, who has worked across the world. He was the director of Cardiff Bay Art Trust and also Head of Visual Arts and Crafts for the Arts Council of Wales.

Ivor Davies, is associated with a stimulating variety of styles but is most recognized as a history painter. Davies could be described as rebellious during the 60s and 70s, being one of, if not the first in the UK to use explosives as part of his artwork. He was the winner of the 2002 Gold Medal for Fine Art at the National Eisteddfod and received an MBE in the New Years Honors List 2007, has exhibited in over sixty solo exhibitions and his work can be found in collections all over the world. Iwan Bala, Artist, writer and philosopher, is a crucial figure in the Welsh arts and cultural scene. Winner of the Owain Glyndwr medal in 1998 for his contribution to the arts in Wales. He has exhibited internationally along with private collections across the UK, winner of the Gold Medal for Fine Art in 1997 and a founder member of The Artists Project.

Tim Davies’ work consists of film, found imagery and sculpture. Winner of the 2003 medal for fine art, he also represented Wales in the 2011 Venice Biennale. And finally, Peter Telfer, a filmmaker based near Machynlleth who runs a television production company by the name of Pixel Foundry and occasionally still takes photographs. He has many photographs of inspirational artists such as Paul Davies on Culture Colony, a website which is specifically for Welsh artists or artists living in Wales. The project was immensely influenced by Paul Davies, and the creator of the website likes to think of the site as a map of Wales Davies would be proud of.

I will bring this essay to an end with the inciting and comforting words of Tim Davies, asked about the current disparate state of the group. They display the spirit of these artists and the power of art:‘…spiritually we’re still together… if the need arises we’ll galvanize together again. The spirit of Beca lasts fundamentally as a political conscience which can be easily stirred.’

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis